The creative writing instructor must be two people: a teacher and an artist. The teacher must set boundaries, assign readings, insist on certain principles of good writing, and address the class as students. The artist must use boundaries to evoke creativity. She must also encourage writing for the real world not simply the classroom and address the students as fellow artists. Like the Driver’s Ed instructor, she must be willing to let go of the wheel but keep her foot near the brake.

The basic tenets of creative writing—imagery and originality—are the essence of every genre, and are the focus of beginning workshops. I construct writing exercises that teach students to “show” not “tell,” writing abstract concepts on the board (love, anger, loneliness) to be concretized and evoked through imagery (the made bed, the raised hammer, the last egg in the carton). In a narrative exercise, we sketch characters by giving them names and describing their cars, their favorite meal, even the contents of their garbage. Poetry workshops open with a discussion of the (attempted) emotional experience and narrow to analysis of the images that best evoke it, while narrative workshops first analyze plot (What did she want? What did she do to get it? What did it cost?), then the use of scenes to tell the story, ending with the examination of more specific details: characterization, setting, and voice.

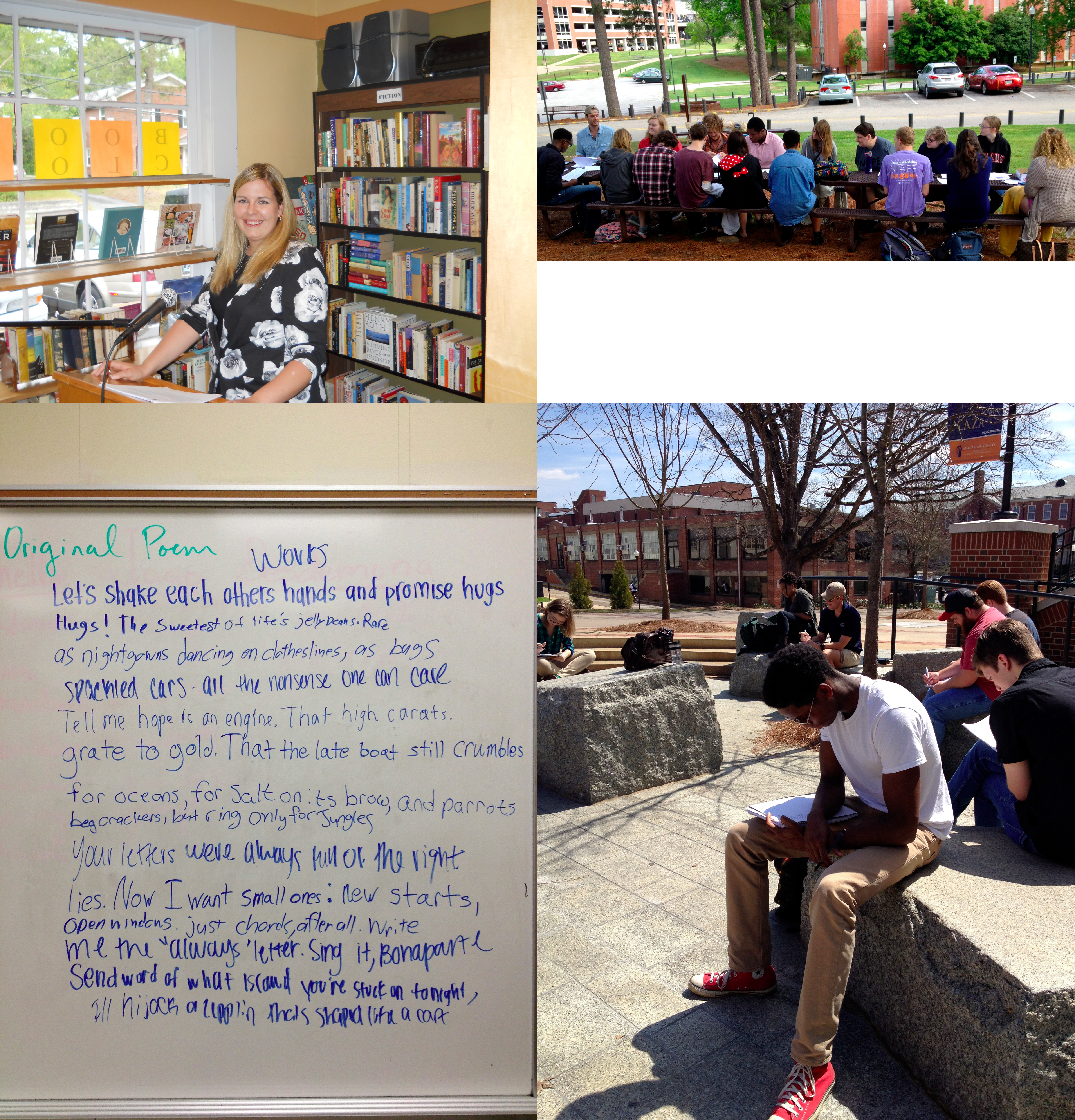

Originality is the other principle of the beginning workshop that every lesson is designed to promote. In a lecture on Haiku, we compose a collaborative poem on the board, each student responsible for one syllable. I ask them to pick a word for its music, not logic. It is always a revelatory moment when they discover thematic patterns from the chaos, proving for themselves that we are meaning-making readers desiring thrills of discovery, not explanation. In crafting narratives, I challenge them to write in settings outside their normal experience by forbidding scenes in bars, churches, dorm-rooms, bedrooms, and offices. Always we seek to identify default ideas and write past them, to avoid cliché.

Teaching students to write in images and pushing them to think in original ways are lessons that, for most, are learned in a semester or two. The real challenge—the lesson that remains central to every workshop, and every act of writing—is honing the writer’s ability to create an emergency and act in it: to create poems and narratives that hook, hold, and heal. The difference between a text and an emergency-text, is as subtle and vital as the difference between a body and a breathing body. Thus the emphasis in advanced workshops shifts from creating well-written texts to creating art.

Making art first requires aesthetic taste honed by reading widely and objectively, especially work unlike one’s own. Reading as a writer means applying a practical rather than analytical mindset: What happens to the poem if we turn the red wheelbarrow blue? What if Gregor wakes up a vermin in first-person p.o.v.? What if Romeo and Juliet had smartphones? We approach texts as mechanics approach cars—isolating and testing systems for function and efficiency. The more hoods we pop, the more we learn fundamentals of the machinery, the necessary versus the decorative. In workshop, we dirty our hands applying the knowledge: first we look for the engine in the piece, later the cup-holders.

In addition to reading widely, making art demands a cultivation of faith: faith that your life matters and is worth thinking about. Faith that your life is connected to every other life—that this is, in fact, the reason art exists. Faith that there are others like you in the world and that your words can touch them and break their hearts just as their words can break yours. I include these “Faith of the Writer” statements in syllabi, but the lesson demands more than lip service. I model my artistic commitments by promoting community in and out of the classroom: holding “writing hours” at a coffee shop every week, encouraging participation in events on campus, creating opportunities to showcase their own writing in meaningful ways. Asking students to put themselves out there, to show up for each other, and showing up for them in turn, sends the message that what they are doing matters. In my experience, students rise to such occasions. Their aesthetics sharpen, their work tightens, and they care more deeply about each other and their own art.

As a teacher, I aim to instill principles of good writing and cultivate taste by introducing students to a wide range of writers, genres, and styles—to model not what to like, but how to like it. As an artist, I aim to teach them how to locate and develop an emergency in their work and give them the tools, encouragement, and confidence necessary to act.

icons at the top right corner of the subsection.

icons at the top right corner of the subsection.